During the first IACCM global virtual conference , organised by Barbara Covarrubias Venegas and her great team, we presented the fishbowl as an inclusivity method to discuss controversial issues online. We decided to present it as a workshop so that participants would get a hands-on direct experience. We started with an overarching question and asked everyone to participate. It was fun for all of us as we experienced it first-hand together. Post-conference we decided to give it a little more background information and provide all of this including a step-by-step guide on how to facilitate this amazing activity online. And here we are.

How did we come up with the 🐟fishbowl as a methodology?

We met at one of the coordinator meetings in Loppiano of the Economy of Francesco (EoF), an event wanted by Pope Francis, which rallies young (under 35) researchers, entrepreneurs and changemakers to come up with a new fair & inclusive economic paradigm. As senior in service (Carlo) and junior coordinator (Giorgia) of the CO2 for Inequalities and Work & Care villages (there are 12 villages total, Source), both responsible for materials and methods, they tried to come up with new ways of interacting and finding innovative and sustainable solutions to communicate, in line with the young crowd they were expecting. The method Carlo proposed to spark a first conversation and make sure everyone had a say was the fishbowl. The live event was supposed to take place in March 2020 (and is now postponed to November 2020) and on day one, Carlo was planning to have a fishbowl with the 30+ participants, part of the pre-event team, and extend it to the 200+ participants at the end of the week. Both villages had already gotten in touch with many of their participants and had started the blending process that would lead to the fishbowl utilizing the eight shields methodology, (which we will keep as a surprise for future blog posts).

As COVID-19 struck and suddenly most of the candidates could not reach Assisi and meet Pope Francis, EoF began to move to an online platform via Mighty Networks. We can easily be considered a global virtual team (GVT) even though, honestly, the more we deal with millennials the less we can pinpoint a title to them. We consider ourselves to be an online Trasformative Community of Change (TCoP) but that might change as well. As in all GVTs or TCoPs, in any case, the virtual nature of the collaboration is crucial for their success even though the process is far from smooth. We learned that virtual teams require greater inclusivity, authenticity, active listening, and, mostly, the capacity to let go of the command and control leadership style to move towards trust and achievement.

The process of shifting to an ‘online only’ reality raised various issues on how to collaborate through different timezones, cultures, organizational behaviors, and how to deal with the emotional strain due to family presence, living conditions and physical aspect. As empathy requirements and the emotional connection began to grow together with the need to be heard, that’s where a fishbowl conversation can replace one-to-one meetings and global exchange. We thus began to experience the fishbowl both as participants and as organizers so sometimes we speak in the name of EoF and sometimes we plan it as EoF.

Ok, so what exactly is a fishbowl 🐟🐠🐡?

Fishbowl conversations are a form of dialog that was born in what is known as unconferences, aka participant-driven meetings that try to avoid standard conference formats such as presentations followed by Q&A sessions. A fishbowl conversation is used when discussing topics within large groups as several people can join the discussion and this allows everyone to participate in the chat (Atkinson, 2009).

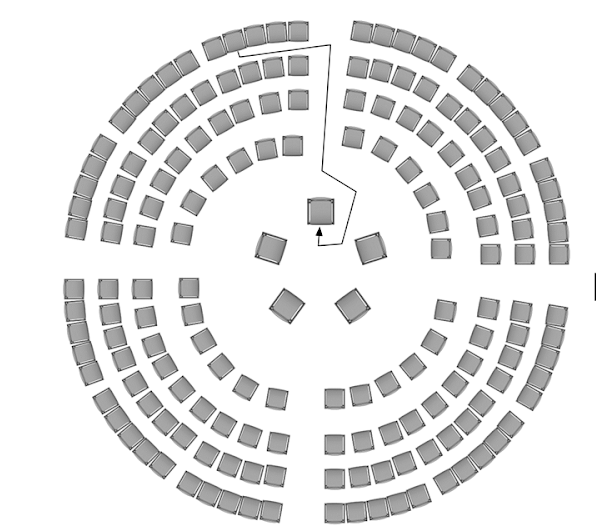

The classic method used in participatory conferences is as follows: four to five chairs are arranged in a circle (that looks just like a fishbowl!), four are occupied, one is left empty. More chairs are then arranged in concentric circles that go around the central loop in the center. There is always a moderator and he or she introduces the topic or poses the first question to initiate the fishbowl. A few participants thus start the fishbowl conversation, while the rest of the audience sits around and listens in to the main discussion. Every two to ten minutes any member of the audience can join the conversation while an existing member of the fishbowl voluntarily leaves and frees another chair. If this doesn’t happen smoothly the moderator can invite someone to move on and rejoin later. Participants therefore enter and leave the fishbowl generating an ongoing flow, making the conversation very interactive. When the set time is over the moderator summarizes the discussion and officially closes the fishbowl.

Variations exist to the open fishbowl model, such as closed fishbowls, where groups of four or five generate a fishbowl and then switch to a new group of four or five participants from the audience, and this goes on until each group has spent some time in the fishbowl. Or, a two-chair fishbowl can be formed where the conversation is sparked by only two people and it keeps moving from there with participants joining in from the audience. Another variation is to use technology to increase participation. This way the participants in the outer circle (OC) can share insights and ideas on a public online forum without needing to wait for their turn or be forced to have an open discussion in the inner circle (IC). Their opinions can be garnered through a post-it gathering or with live or digital voting. In this variation, an open seat is left available for OC participants, so that they can join the fishbowl if they want to.

Why use a fishbowl?

An advantage of a fishbowl conversation is that it shortens distances between the speakers and the audience and is useful for larger groups. The focus is all on the conversation that emerges as the participants are the custodians and curators of the conversation. The initial questions for a compelling discussion need to be accurately prepared as well as the conversation starters, which must be carefully picked- participants must know how to listen before speaking. The success of the fishbowl is dependent on the moderator who ensures that individuals, either those beginning in the fishbowl or joining the discussion at a later time, do not dominate the talk or take it off track. Fishbowls are not meant to reach consensus but instead generate an intimate and spontaneous conversation used for building dialogue between participants. Also, the open-ended questions are meant to explore what was not known before.

The fishbowl in the virtual space.

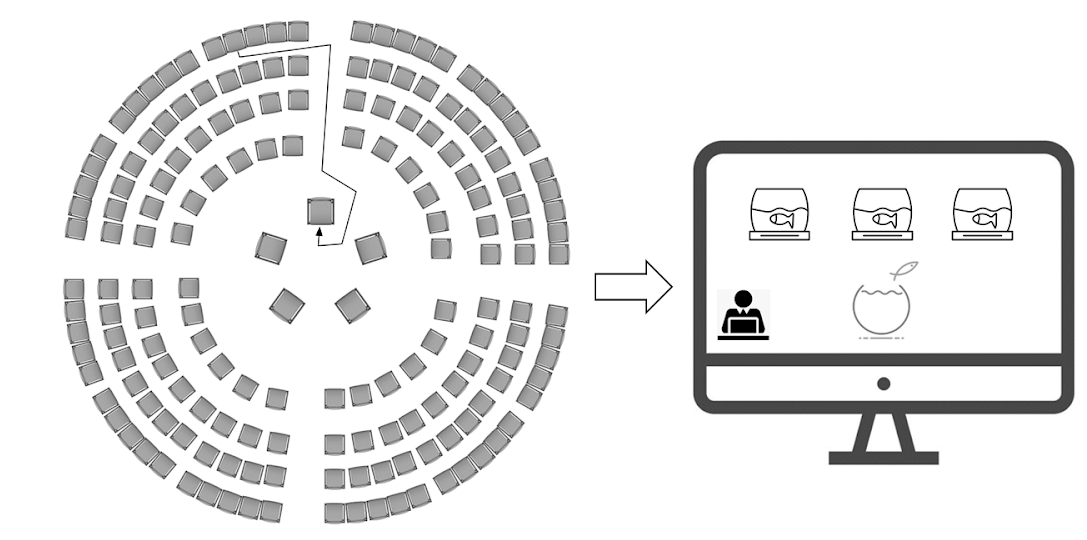

Online, with virtual participants, the framework does not vary much. A group of experts, guided by the moderator, start a conversation where participants can join in at any time (see figure below). This allows multiple voices even in difficult contexts where there is limited psychological safety and potential speaking inhibitions. As more and more conferences and meetings move online, the fishbowl helps to maintain attention levels and generate positive deviance as it focuses the entire group’s attention on the main discussion. It is a useful engaging alternative to presentations or panel discussions as it calls for direct conversations with experts, providing participants with an interactive platform for discussing controversial issues. In our case they were used for collaboratories, such as the LiFT study, and issues would range from post-war or post-apartheid contexts to managerial environments where we wanted to work on relational tensions between people from different departments.

How to facilitate a virtual fishbowl?

👉 You start the call with everybody’s microphone muted and video on. The Host makes a brief introduction and then asks everybody to switch their videos off. Only the Conversation Starters keep their video on and engage in an opening dialogue to introduce the fishbowl themes (3/5 minutes each). Technical note for zoom: if you ask participants to “hide non-video participants” by clicking on the three dots of their own image, and if everybody follows this instruction, the participants will only be able to see the current discussants in the middle of the fishbowl!

👉 The moderator then asks all participants to provide a comment and a question to keep the conversation going. Participants can then independently (or with the help of the moderator if needed) switch their video on when they want to talk and follow the order of appearance. The goal is to have a maximum of 4 or 5 people engaged in the conversation (with their video on).

👉 When a participant starts his or her video (to enter in the conversation), someone else should stop his or her video (to exit the conversation) to ensure there are a maximum of 4 or 5 people engaged (3-4 plus the moderator) actively in the conversation.

👉 Fishbowl contributions should be kept within 1 minute or so and should end with a follow up question so that other people in the fishbowl (or willing to enter it) can pick up on that. Participants may re-enter the fishbowl more than once, of course. The one minute guideline is to keep the conversation flowing from fish to fish, rather than having one shark. The objective is to have an organically growing conversation. It is fundamental that people feel that they are the initiators and custodians of the conversation.

☝ Note: the fishbowl may be slow to start but you can trust our word that it always gets sparked sooner or later and it is hard to stop the flow.

☝ N.B. ideally you want to be in touch beforehand with at least three participants as conversation starters and send the guidelines to the rest of the group.

Fishbowl examples.

A recent example of the virtual fishbowl is the #goodaftercovid19 initiative. This process uses the pandemic as a stimulus to gather the 20% participation needed to reach a tipping point that unlocks the new connectedness paradigm by creating a common platform where people can meet to discuss and build a better future and to correct many of the pre-existing weaknesses the COVID has exposed.

In the first online fishbowl event, building on sustainable development goals (SDGs), forty experts from diverse backgrounds discussed ways to correct imbalances, improve collective systems, and strengthen interconnected relationships. Nine topics were defined by the first conversation: Define a new Leadership paradigm; Reinstate the real purpose of Economy; Redesign the Internet for better democracies; Trust science and spirituality, not power; Make human essential needs accessible to everybody; Implement the Theory of Change for the SDGs; Move beyond “Competition vs Collaboration” towards “Co-opetition”; Weave an Intergenerational Pathway towards a Thriving Society; Transform All Education into Issue-Based Learning.

The group proposed that the world after this crisis is dramatically improved and that business doesn’t go back to the ‘business as usual’ approach. Responsibility must be more spread out, beginning at an individual level and then shared amongst companies, industries, and governments in a civil responsibility perspective (Bruni, 2010; Zamagni, 2007).

Sergio Caredda provided us with his “Good After Covid19: from crisis to global opportunity” a great live sample fishbowl. Also to be watched on YouTube here.

How the fishbowl can help a shift.

Meadows (1997) mentions that the highest leverage point to intervene in a system is the mindset or paradigm out of which the system arises and Tsao and Laszlo ( 2019) state that transforming our consciousness is the most effective tool we have for unlocking local and global change (Nigri & Agulini, 2019). Practices that develop connectedness (VanderWeele, 2017), such as a fishbowl conversation can awaken a desire for change in ourselves as the solution lies within. Changing people at a deep intuitive level provides the keys to greater effectiveness and wellbeing which can drive towards integral post-COVID ecologies (Bergoglio, 2014).

The fishbowl is an excellent instrument to discover new insights by allowing a conversation to develop through a powerful and open-ended question that does not have to have a linear answer. The point of an online fishbowl, especially in a volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA) context would allow multiple voices in difficult contexts whit limited psychological safety and high inhibition to speak and could spark more open conversations and fewer panels with pre-cooked truth.