Become a #virtualspacehero 🚀

The future of work and the role of education

I recently read a New York Times opinion piece by Thomas Friedman, author of The Lexus and the Olive Tree (1999) and The World is Flat (2004), as well as other books and articles that highlight the trajectory of globalization. In “After the Pandemic, a Revolution in Education and Work Awaits” Friedman shares insights from an interview with Ravi Kumar, the president of the Indian tech services company Infosys, whose headquarters is in Bangalore. In this article both men explore ideas regarding the future of work and of education in preparing students for employment. The complexity of what is to come requires us to invest resources and time in rethinking education and career readiness.

As an international and experiential learning educator, I’ve been following Friedman for some while. Since I’ve been developing internship programs for 20 years and have seen the transformation of so many industries during this time, this piece made me reflect upon the jump from in-person internships to virtual ones. While there will always be industries that require in-person labor, virtual work is the way that many industries will operate in the future. In particular what resonated for me was how important continuous learning and working will be for the future professionals I help:

“Your children can expect to change jobs and professions multiple times in their lifetimes, which means their career path will no longer follow a simple ‘learn-to-work’ trajectory, as Heather E. McGowan, co-author of The Adaptation Advantage, likes to say, but rather a path of ‘work-learn-work-learn-work-learn.’” – T. Friedman (2020)

When the pandemic hit, students who had been planning on completing summer 2020 internships found themselves without that very necessary step in their university education: taking the theoretical knowledge of the classroom and applying it to the work world in an academic internship. As Goldie Blumenstyk (2020) noted in The Chronicle of Higher Education article “Students’ Internships Are Disappearing. Can Virtual Models Replace Them?”, during those months some students self-organized and launched a website, internfromhome.com, enabling themselves and others to connect with companies for virtual internships, and not lose out on this opportunity. She describes these types of initiatives as providing emergency measures to fill a very pressing need.

International internship redesign – lessons from the field

During those same months my organization embarked on an integral redesign of internships to meet the needs of our university partners. EUSA Academic Internship Programs is a not-for-profit international education organization that has been working for 35 years with colleges and universities to implement customized and faculty-led study abroad programs in London, Dublin, Madrid, Paris and Prague. Our Virtual International Internship Program has been designed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic’s restriction to student mobility. Once study abroad mobility limitations are lifted, this program will run parallel to the usual offerings because it satisfies a new educational demand: preparing undergraduate university students for the virtual workspace and for collaboration in virtual teams. It also allows students who may not be able to go abroad the chance to experience working on an international level as part of a globalized workplace, thus helping to make the advantages of study abroad more accessible to all. If there is one thing we’re sure of, the pandemic has taught us that multiple workplace models are necessary and we need to help our students be successful in their ability to adapt, work and learn.

“EUSA creates meaningful learning experiences in new places and new spaces.”

What are necessary pieces of a successful virtual internship design?

Virtual international internships present a unique opportunity to gain professional experience and preparation for the new world of work. Some design considerations with regards to successful virtual internships include:

- Goal setting from a multi-stakeholder’s approach

- Clearly thought-out program design based on solid learning theory: creating the learning journey

- Selecting the appropriate tech to enable meaningful interaction opportunities

- Professional and intercultural learning opportunities

Goal setting from a multi-stakeholder’s approach

In order for the virtual internship to work, it must be conceived as a collaborative program based on the collective goals of each of the stakeholders. The learning objectives are defined in cooperation between the student, the university, the internship supervisor and internship provider.

Undergraduate university students are required to identify personal and professional development goals. In order for universities to deliver upon their mission to provide adequate practice that will lead to real life job skills, the study abroad advisors need to understand and be able to articulate to students which transferable skills will be achieved and measured to meet their academic requirements. For the host company, the internship supervisor needs to identify areas in which meaningful work can be carried out virtually by someone who is starting out professionally and who may also be in a different time zone and have differing language skills. The internship provider needs to be aware of all of these goals, inform the various stakeholders of the requirements and available options, and ensure a design that satisfies each of them.

Solid learning theory to shape the learning journey

An internship program should allow students from all preferred learning styles (active, theoretical, reflective, and pragmatic) to put into practice knowledge in action.

Kolb’s Learning Style Model (1984) shows us that in order to learn we need to work with or process the information we receive. Kolb says that we can start learning from one of two places:

- a direct and concrete experience: active student

- an abstract experience, such as that which we have when we read about something or when someone tells us something: theoretical student

The experiences we have, concrete or abstract, get transformed into knowledge when we develop them further through one of these two procedures:

- actively experimenting with the information received: pragmatic student

- reflecting and thinking about them: reflective student

According to Kolb’s model, optimal learning is the result of processing the information through a cycle that touches upon all four phases.

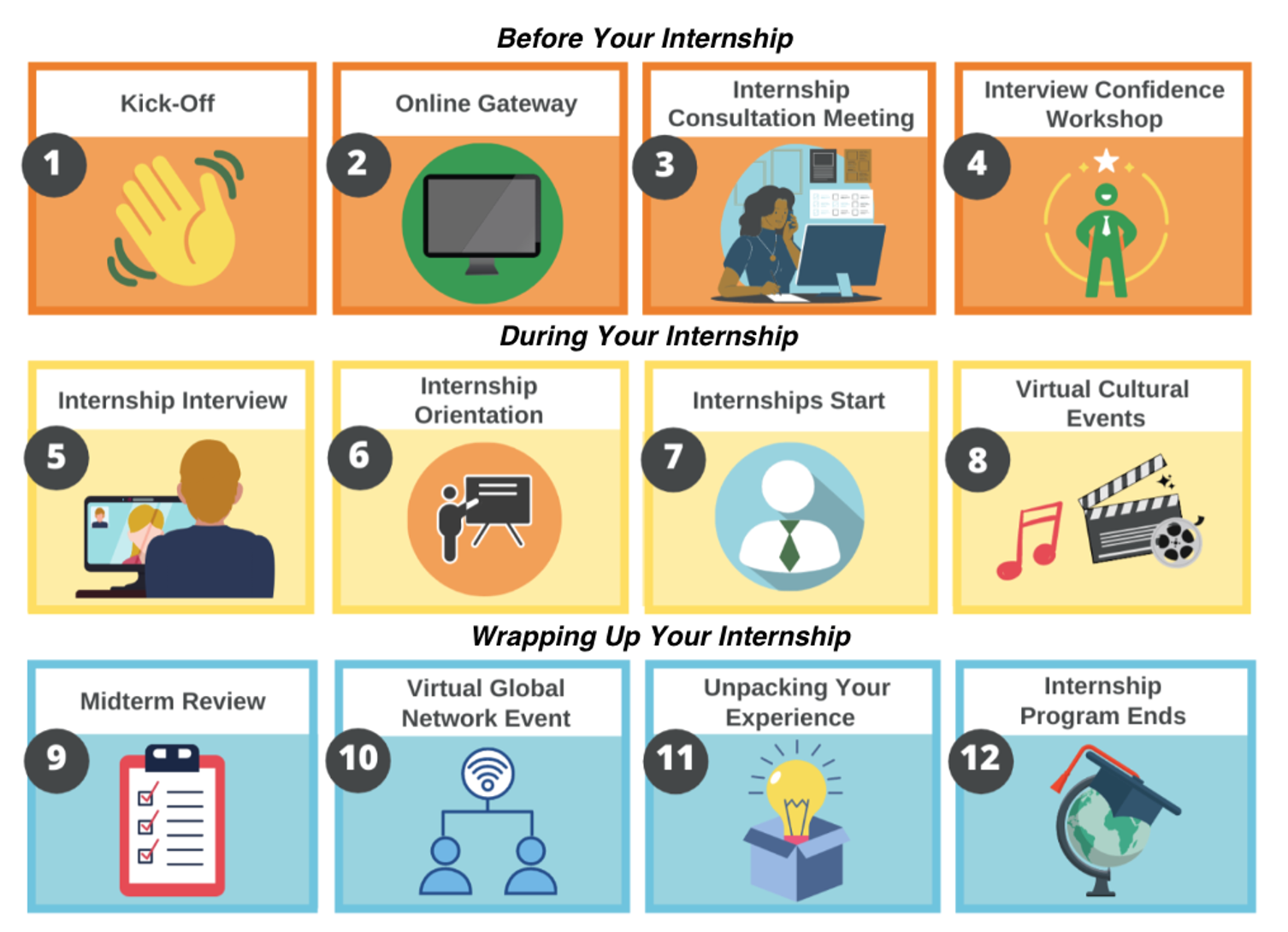

EUSA Academic Internship Experts Student Experience Roadmap, used with permission.

At EUSA we have taken Kolb’s model and applied it to a learning journey. We’re facilitating the environment in which the students apply what they’ve been seeing in the classroom into a real-life work environment. Our design has them go through all four stages. It starts off with onboarding to the program, opportunities to learn new information and skills for working virtually, coaching and interview preparation, coordinating with supervisors the job tasks and responsibilities that keep the learning cycle in mind, working in global virtual teams, intercultural learning activities, as well as a reflective framework for the students, supervisors, internship coordinators and university advisors to think about and gain insights into the learning on the program.

Selecting appropriate tech for meaningful interaction

The online format provides us with new possibilities. We’re able to offer more to our students, universities and host companies in the virtual space because we don’t have the same physical and economic constraints. Creating a collaborative environment in order to foster a sense of community and off-set isolation is important in order to increase motivation to complete the program. Our face-to-face time with students, supervisors and university advisors has to provide added value beyond simply transmitting information. We need to carefully consider the tech we use to engage with the stakeholders. My recommendations are:

- Zoom or another videoconferencing platform for one-on-one check-ins with students, supervisors and university advisors

- Zoom combined with Menti word clouds or polls, as well as breakout rooms during group events

- Miro Boards to work collaboratively during group events

- Padlet and Flipgrid for guided asynchronous assignments and interactions

Professional and intercultural learning opportunities

Online work takes on the nature of chunks or modules. A project gets broken down into pieces that need to be delivered at set dates and times, and meetings tend to be more agenda-driven. Because the nature of virtual work is more task based, whatever spontaneous cultural and linguistic learning happened in person now needs to be purposefully facilitated.

The virtual international internship program should supplement the internship work with activities for professional development as well intercultural learning events. At EUSA we’ve included professional development workshops and cultural and intercultural activities to provide the background for working across cultures. Students get to know more about the culture of their host company while learning about their own one(s) as well. In the case of EUSA, because we operate in 5 countries, the virtual space has allowed city or country specific intercultural learning to be extended into a pan-European intercultural learning experience. Specifically, we focus on virtual etiquette and team building skills, networking and identifying and appreciating cultural differences. Effective international internships need to curate professional and intercultural learning opportunities.

Conclusion

If there’s one lesson from the field that I hope to leave with you it’s how important it is to really think out and test the proper design. It requires investing time and resources into research around self-directed learning, into the skills and tasks offered by virtual work, into how online learning and working communities are created, and into how to set systems in place to ensure that all the stakeholders’ goals are met. A well-designed virtual international internship program is the result of a complex process that matches how the future of work is evolving. Like my students’ career path, this new program is the result of the process of ‘work-learn-work-learn-work-learn.’

💡 Resources 💡

Blumenstyk, Goldie. (May 13, 2020) “Students’ Internships Are Disappearing. Can Virtual Models Replace Them?” The Chronicle of Higher Education: https://www.chronicle.com/newsletter/the-edge/2020-05-13

Friedman, Thomas. (October 20, 2020) “After the Pandemic, a Revolution in Education and Work Awaits”. New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/20/opinion/covid-education-work.html

Kolb, David (1984). Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

About the author

Almendra Staffa-Healey is an intercultural trainer and international and experiential learning educator. She is the Madrid Director of EUSA Academic Internship Programs and the Co-Founder & Director of Intercultural Understanding. She has been working for 20 years in the field of international education, experiential learning through internships, and intercultural competency development for education and professional purposes. She has a BA in Art History and Education and two Masters’ degrees, one an MBA and another in Anthropology. She is also an Intercultural Development Inventory Qualified Administrator and a Senior Facilitator of Personal Leadership Methodology. She is passionate about cross-cultural understanding and mindfulness. At present she is the SIETAR España President, a part of the Society for Intercultural Education, Training and Research.

0 Comments